Why Finance Won, Everyone Else Lost

Why Corporate America has become obsessed with stock buybacks

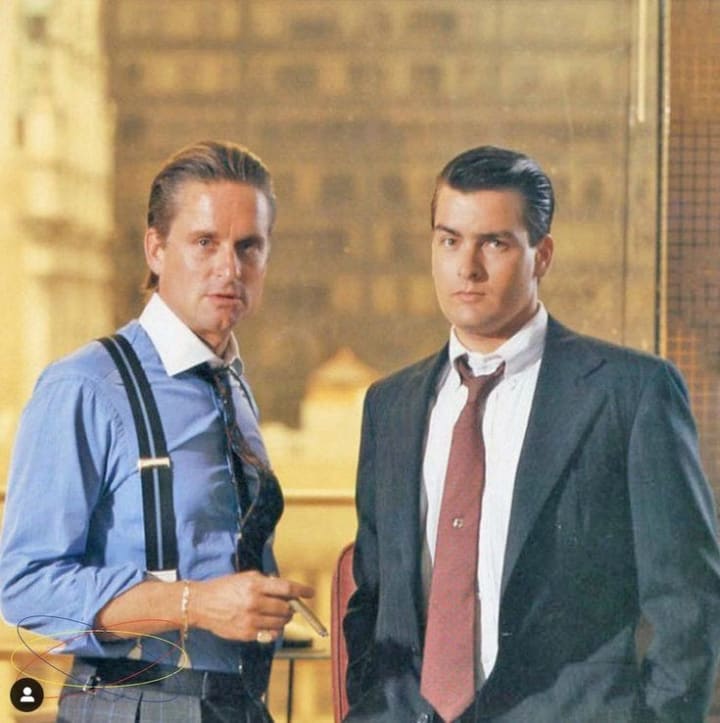

Let’s time-travel to the 1980s. big hair, bigger shoulder pads, and Wall Street guys doing lines of… ambition.

Back then, the “shadow banking” world — hedge funds, private equity firms, family offices — controlled assets worth about 40% of America’s GDP.

Those same institutions now control assets worth 200% of GDP. They’ve quintupled their grip on the economy. Throw in traditional banks, and you’re looking at over 300% of GDP under financial sector control.

Domestic financial assets in America alone are now valued at $145 trillion. That’s roughly 500% of what the entire economy produced in 2024.

Now, in theory, this isn’t necessarily sinister. The financial industry plays a genuinely important role in a healthy economy. It’s the grease that keeps the gears turning. It helps businesses grow. It provides liquidity — meaning you can actually sell stuff when you need to.

It lets ordinary people buy houses and cars without saving for decades first. It manages risk, spreads it around. And it gives people with extra savings somewhere productive to park that money while earning a return and, ideally, growing the economy for everyone.

Okay, so the financial industry has gotten massive. But is that actually a problem?

Look, every industry’s goal is to grow and make money. That’s just capitalism doing its thing. It only becomes a problem if that growth is happening at everyone else’s expense.

Hedge funds. Quant firms. Private equity. Distressed debt. High-frequency trading. Market makers. Secondaries funds. Structured credit. Buy now, pay later. SPACs. Peer-to-peer lending. Cap funds.

Most of these barely existed 30 years ago. Today, they’re each running their own multi-billion-dollar empires.

A lot of these functions used to live inside traditional banks. But then some sharp financiers realized something. If they spun off on their own and started independent firms, they could take on way more risk — and make way more money — without dealing with all those pesky regulations that come with being a bank.

So today, the boring old banks are basically a footnote in the financial ecosystem.

And we haven’t even mentioned the wild world of crypto firms yet — though honestly, their playbook is identical to everyone else’s: shuffle money around, cross your fingers, hope it multiplies.

While tech companies dominate the headlines with their high valuations, it’s actually finance that’s been raking in the cash.

In last quarter of 2024, the financial industry captured a record 21% of all corporate profits in America. Think about that. One out of every five dollars in profit went to finance.

But where things get really strange.

The finance game has attracted way more players. But it’s not just traditional financial firms anymore. Regular companies — ones that are supposed to make actual things — have started cosplaying as financial institutions. Because that’s where the real money is.

America’s public corporations = Mini Hedge funds.

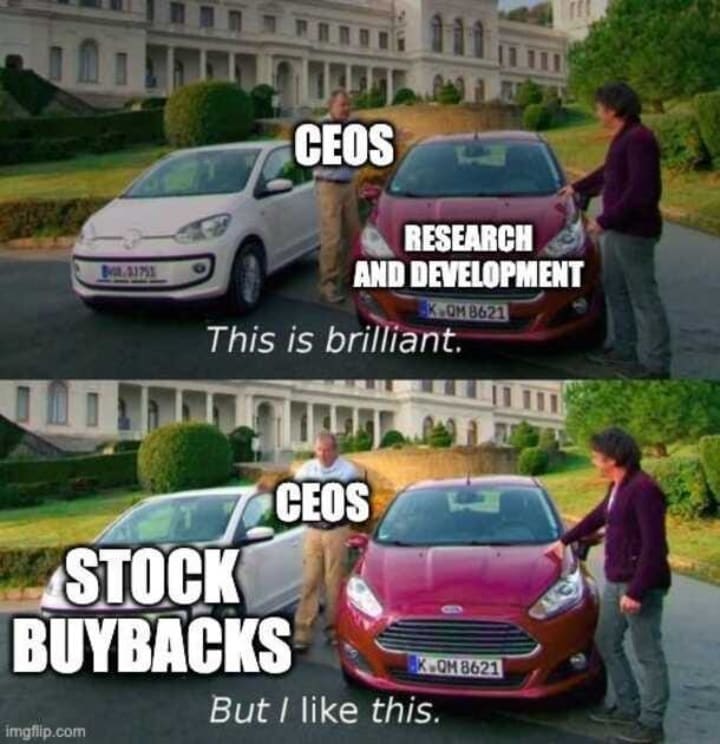

Over the past 40 years, the corporate playbook has become obsessed with one move: stock buybacks.

A company uses its cash to buy its own shares. This creates artificial demand (hey, someone’s buying!) while shrinking the supply of available shares. Economics 101 kicks in: more demand + less supply = prices go up.

But Buying back shares makes key metrics like “earnings per share” look better — not because the company actually earned more through brilliant products or smart cost cuts, but simply by doing math differently. Same profit ÷ fewer shares = prettier numbers.

The winners

Existing shareholders who watch their stock prices climb. And executives whose paychecks are tied to short-term stock performance.

The losers

Well, let’s talk about that.

Is finance still doing its actual job — you know, enabling real economic growth?

Because when companies blow all their cash on stock buybacks, that’s money that’s not funding research and development. Not creating better products. Not building the future.

It gets even more ridiculous.

Companies have started borrowing huge sums of money specifically to buy back their own stock. They’re going into debt to play the stock market with themselves.

At this point, these aren’t really businesses anymore. They’re leveraged buyout funds that only invest in one asset: their own stock. It’s corporate financial narcissism, and it’s not exactly a recipe for long-term success.

This whole system sucks up capital that could be funding scrappy new companies trying to break into the market. The money’s all locked up in established corporations playing elaborate financial games with themselves.

If you corner any economist at a party and ask them what the financial industry is supposed to do, they’ll paint you this nice little picture:

There’s a farmer who wants to grow food but doesn’t have the cash for land and seeds. So they borrow money from a bank, plant their crops, sell the harvest, pay back the loan with interest, and boom — everyone wins. The farmer gets their business off the ground. The bank makes money on interest. And society gets more food.

It’s a beautiful story.

Except that’s not what’s actually happening.

What’s really happening is that existing farms are taking out loans to buy back stock from their shareholders — instead of buying new equipment or experimenting with better crops — because gaming the financial markets is more profitable than actually producing food.

The finance industry has gotten so big that it’s actually discouraging innovation instead of funding it. The very thing it was supposed to enable.

So who’s actually paying for all the innovation we keep hearing about?

Well, statistically speaking: you are.

Government subsidies, research grants, tax breaks, and other public payments to encourage business innovation have more than quadrupled in OECD countries since 2000.

You’re probably thinking of the obvious examples. SpaceX. Defense contractors. EV manufacturers getting fat checks.

But there’s literally a booklet — like, an actual giant booklet — filled with different tax credits available to businesses to “invest in themselves.”

And some of these need to be read with a healthy dose of irony. There’s a tax credit for coal exploration listed in the same breath as tax credits for low-emission energy and carbon sequestration. It’s like having a “quit smoking” pamphlet that also includes a coupon for Marlboros.

But Direct government-funded research has dropped considerably over the decades.

The idea — at least in theory — was that instead of taxpayers directly funding government labs to do research, we’d just give private companies tax incentives to do it themselves. Same research, less bureaucracy, everybody wins.

But there’s a pretty major problem with this.

When the government made a research breakthrough back in the day — think the internet, GPS, touchscreens — anyone could use it for commercial purposes. The technology was in the public domain. So the benefits spread quickly. Everyone got a piece of the pie.

But when a private company makes a discovery, even if it’s bankrolled by generous taxpayer-funded incentives, they own that intellectual property. Which means only they can profit from it. The rest of us? We get to wait until the patent expires or pay whatever licensing fee they demand.

Let’s talk about Sand Hill Road

It’s a 5.6-mile stretch of asphalt running through Palo Alto, Menlo Park, and Woodside in California. Doesn’t sound like much. But this road is home to Sequoia Capital, Andreessen Horowitz (a16z), Menlo Ventures, and Blackstone’s California headquarters.

All massive venture capital firms.

These are the institutions that have essentially taken over the job of providing early-stage funding to promising startups. The sheer volume of money flowing out of these offices has earned Sand Hill Road a nickname: the Wall Street of the West.

Right now, these firms are pouring billions into anything with “AI” slapped on it.

Ten years ago it was the same playbook, but with crypto.

A decade before that was user networks and the “sharing economy.”

And a decade before that was Literally anything with “.com” in the name.

These firms don’t necessarily believe these are the best businesses to invest in. They just know they’re going to be the easiest to flip into public markets.

If Wall Street is hungry enough for the next hot trend, venture capitalists can sell their early stakes before the companies even turn a profit. Sometimes before they generate any revenue. Occasionally before they even have a working product.

Just hype, a pitch deck, and a good story.

Let’s zoom out for a second.

Businesses still eventually need to deliver an actual product or service to customers. That hasn’t changed.

But what has changed is that in modern markets, a “business plan” has essentially morphed into a marketing campaign — and what they’re really trying to sell isn’t a product.

It’s their own stock.

About the Creator

Arsalan Haroon

Writer┃Speculator

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.