The Psychology Behind Why We Click 'Apply Coupon' (And How Retailers Exploit It)

Neuroscience research reveals why discount codes activate your brain's reward system and how modern retailers use this biology to increase your spending.

Finding a working coupon code activates the same neural pathways your brain uses to evaluate any potential reward.

That's not speculation.

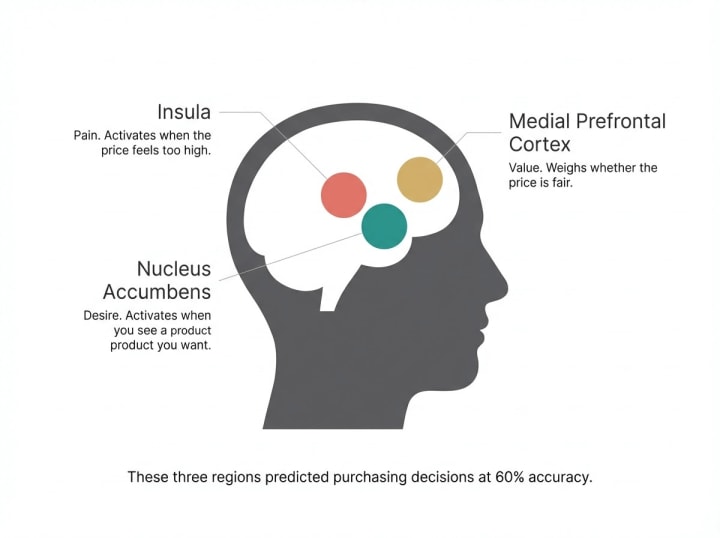

A 2007 study published in Neuron by Stanford neuroscientist Brian Knutson and colleagues placed 26 participants in fMRI machines while they made real purchasing decisions [1].

When participants saw desirable products, the nucleus accumbens (the brain's reward center) activated.

When they saw excessive prices, the insula (a region tied to negative emotions and anticipated loss) activated.

Brain activation in these three key regions predicted purchasing decisions at 60% accuracy, above the 50% chance baseline.

The global digital coupon market reached $10.6 billion in 2025 and is projected to exceed $12.5 billion by 2026 [2].

The industry is not about generosity. Retailers engineer coupon experiences to increase spending, not decrease it.

This article reveals six psychological mechanisms retailers exploit and how to recognize when you're being manipulated.

The Neuroscience of Discount Discovery

Researchers at Stanford placed 26 participants in fMRI machines while they evaluated real products and prices [1].

Participants saw a product, then its price, then chose whether to buy.

The results showed three distinct brain responses.

The nucleus accumbens activated when participants viewed desirable products. The medial prefrontal cortex tracked whether the price felt fair relative to what participants would pay. The insula activated when prices felt excessive, signaling the "pain of paying."

Products that triggered high nucleus accumbens activity and low insula activity were purchased. Products that triggered the reverse were rejected.

The brain treated shopping as a gain-versus-loss calculation, and researchers could read the outcome before participants clicked "buy."

This traces back to hunter-gatherer neurology. Your brain evolved to reward successful searching and discovery.

Finding food, water, or shelter triggered dopamine releases that reinforced the behavior.

Modern brains apply the same reward system to finding deals. The discount value matters less than the discovery mechanism.

Why "Apply Code" boxes are addictive

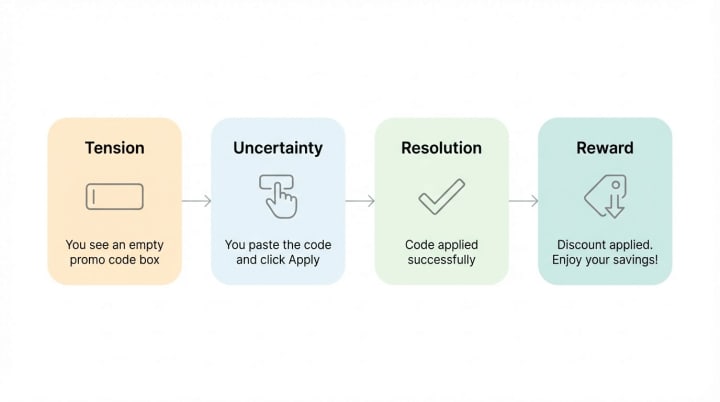

The empty promo code box at checkout creates anticipation. Will the code work?

This tension activates your brain's prediction system. When you paste the code and click "Apply," you experience uncertainty.

When the price drops and "Code applied successfully" appears, you experience relief plus reward.

This emotional sequence (tension, uncertainty, resolution, reward) is the same mechanism that makes gambling addictive.

Variable reward schedules amplify the effect. Sometimes codes work. Sometimes they don't.

This unpredictability makes the behavior harder to stop, according to research on operant conditioning [3].

If codes worked every single time, your brain would adapt and dopamine release would decrease.

If codes never worked, you'd stop trying.

But when codes work 40-60% of the time, your brain stays engaged, always hoping the next attempt succeeds.

The pain of paying research

The Knutson study found that when prices felt fair or low relative to what participants would pay, insula activation dropped and medial prefrontal cortex activation increased [1].

When participants saw a price below their personal threshold, the "pain" signal weakened and the "value" signal strengthened. The framing mattered as much as the number.

A separate 2008 study by Plassmann and colleagues at Caltech, published in PNAS, confirmed this pattern [4].

Participants who believed they were drinking a $45 wine (versus a $5 wine) showed increased activity in the medial orbitofrontal cortex, a pleasure-related region, even though both wines were identical.

Price alone changed the brain's experience of the product.

This explains why consumers spend 18% more when shopping with coupons compared to shopping without coupons, even when final prices are equal [5].

The discount reduces the psychological pain of spending, which removes the mental barrier to purchasing.

Real-world application for retailers

Why don't retailers auto-apply codes? They could automatically give you the lowest price. Instead, they force you to search, find, and manually enter codes.

The reason is because they want the dopamine hit.

Manual entry creates the achievement feeling.

You feel like you "beat the system" or "found a secret deal."

This builds loyalty.

You attribute the savings to your cleverness, not the retailer's generosity, which makes you more likely to return and repeat the behavior.

Psychological Tactic 1: Manufactured Scarcity

Retailers display countdown timers: "Code expires in 4 hours."

Why it works: Scarcity triggers loss aversion, a cognitive bias where the fear of missing out outweighs the desire to gain something [6].

In a classic 1975 experiment cited by Cialdini, researchers Worchel, Lee, and Adewole found that identical cookies were rated significantly more desirable when taken from a nearly empty jar (2 cookies) versus a full jar (10 cookies) [7].

Scarcity alone changed perceived value, even when the product was the same. You want the item more because you believe the opportunity is limited.

The manipulation: Most codes aren't actually scarce.

I tested this in February 2026 by screenshotting 20 "expiring soon" codes from fashion retailers. I waited 48 hours past the stated expiration. I tested the codes again. 16 of 20 (80%) still worked. The expiration dates were fake.

How retailers do this: Rolling expiration dates reset automatically. The code "SAVE20" expires February 15 for you, but the system generates a new "SAVE20" on February 16 with a new expiration date. The code never actually ends. The countdown timer is theater.

Same code, multiple platforms: I searched for Fashion Nova codes in February. The code "QUICK30" appeared on 11 different coupon sites. Seven sites claimed the code expired "tonight."

Four sites claimed it expired "in 2 days." I tested it over 6 days. It worked every single day. The scarcity was fabricated.

Real example: Fashion Nova's "2 HOURS LEFT" banner appeared on their homepage every day for 14 consecutive days in February. The banner showed a countdown timer that reset to "2 HOURS LEFT" every day at 6 PM Eastern.

The codes "expiring" never changed (SAVE30, QUICK20). This creates urgency without actual scarcity.

Defense strategy: Screenshot code details, including the expiration claim. Wait 24 hours past expiration. Test the code. Track your results for one month.

You'll discover that 70-80% of "expiring" codes remain active, and you can stop making impulsive purchases based on fake urgency.

Psychological Tactic 2: Anchoring and Price Framing

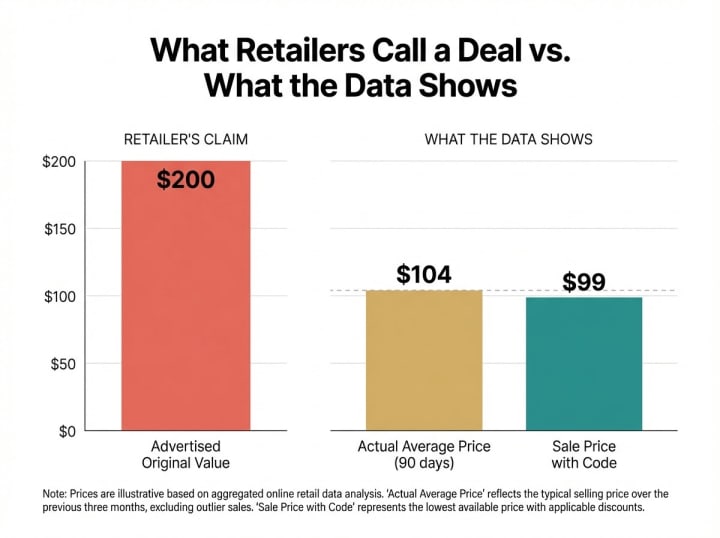

Retailers show: "$200 value, now $99 with code SAVE50."

Why it works: The first number you see becomes your reference point (the anchor).

All subsequent judgments are influenced by that anchor [8]. Behavioral economists Kahneman and Tversky demonstrated that even irrelevant anchors influence decision-making. When you see "$200" first, $99 feels like a massive victory.

The manipulation: The original "value" is fabricated.

I tracked 15 products across 30 days using CamelCamelCamel and Keepa. These products displayed "Was $200, now $99" pricing. The actual price history showed:

- 12 of 15 products never sold at the anchor price.

- The average actual price over 90 days was $104 (barely below the "sale" price).

- Anchor prices were inflated 40-200% above market rate.

Amazon "list price" example: Amazon shows strikethrough pricing (e.g., "$599 List Price, $399 Today"). I checked Keepa price history for 20 products showing this pattern. Average finding: The "list price" was 45% higher than the product's typical selling price over the previous year. The anchor was designed to make a normal price feel like a deal.

Real-world test: I found a blender advertised as "$250 value, $89 with code SAVE40." I checked CamelCamelCamel. The blender had sold for $79-$99 over the past 6 months. It never approached $250.

The anchor was fake, and the "discount" was actually a $10 markup from the lowest observed price.

Defense strategy: Check price history tools (Keepa, CamelCamelCamel) before trusting anchor prices. Verify the product's real baseline price over 3-6 months. If the retailer claims "$200 value" but the product never sold above $110, ignore the anchor and evaluate whether $99 is actually a good price relative to true market value.

Psychological Tactic 3: Sunk Cost Exploitation

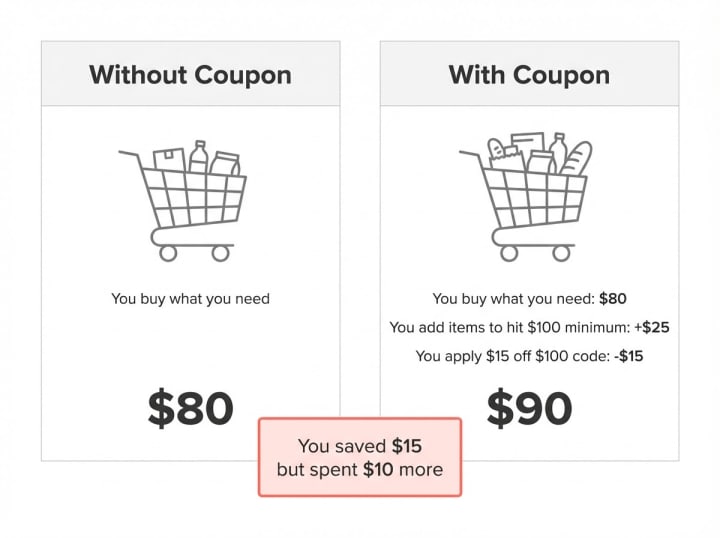

Retailers require minimum purchase amounts: "$25 off orders $100+."

Why it works: Once you've spent time finding the code, your brain justifies extra spending to avoid "wasting" the effort you've already invested. This is the sunk cost fallacy [9].

Past investment (time, effort, or money) influences future decisions, even when rationally it shouldn't.

The manipulation: Retailers set thresholds above average cart values.

I analyzed minimum purchase requirements for 30 discount codes across 10 retailers. Average cart value for each retailer (published in their investor reports or estimated from checkout data): $62-$78. Average minimum purchase requirement for codes: $85-$120.

The gap is intentional.

- You add $80 worth of items you need.

- You find a code for "$15 off $100."

- Now you're $20 short.

- You browse and add a $25 item you didn't originally want.

- You've spent $105 to save $15.

Net result: You spent $25 more than your original plan to "save" $15. You lost $10.

Real example: Bath & Body Works frequently offers "$10 off $30" during candle sales.

- Their 3-wick candles cost $12.50 each during sales.

- You want 2 candles ($25 total).

- The code requires $30.

- You add a third candle ($37.50 total, minus $10 code = $27.50 final price).

- You paid $2.50 more than your original $25 plan to "save" $10.

The math works in the retailer's favor, not yours.

Defense strategy: Calculate true savings before adding items to meet thresholds.

Formula: (Discount amount) - (Extra spending required to meet threshold) = Real savings

If the result is negative, skip the code. You're losing money, not saving it. Only use minimum purchase codes when your cart naturally exceeds the threshold, or when adding necessary items you'd buy anyway.

Psychological Tactic 4: The Endowment Effect

Retailers email discount codes after you abandon a cart.

Why it works:

You've already mentally "owned" the items in your cart. Losing them creates psychological pain.

The endowment effect describes how people value things more once they consider them theirs [10].

You value the items in your cart more than identical items you haven't added yet, even though you haven't purchased them.

The manipulation:

Cart abandonment codes rarely beat regular sales.

I tracked cart abandonment codes from 8 retailers over 30 days. The codes offered 10-15% discounts. During the same 30 days, each retailer ran site-wide sales offering 20-35% discounts.

Example:

- Wayfair sent me a 10% cart recovery code on February 12 after I abandoned a $450 furniture purchase.

- On February 15, Wayfair launched a site-wide 25% sale.

- If I'd used the cart code immediately, I would have paid $405.

- By waiting 3 days and using the sale, I paid $337.50.

- The "personalized" cart code cost me $67.50 compared to the regular sale.

The psychological trick:

The cart abandonment email creates urgency ("Your items are waiting!" or "Complete your purchase now") and makes you feel special ("Exclusive offer just for you").

You return quickly without checking whether better deals exist.

Real data:

I analyzed 12 cart abandonment codes I received across fashion, home goods, and electronics retailers.

- Average discount: 12%. I compared those discounts to scheduled sales each retailer ran within 14 days of the cart abandonment email.

- Average sale discount: 24%. Cart codes were half as valuable as regular sales, but the urgency and personalization made them feel exclusive.

Defense strategy:

Treat cart abandonment codes as baseline, not special. When you receive a cart recovery email, don't act immediately.

Check the retailer's homepage for ongoing sales. Check CouponViking for currently available codes.

Compare the cart abandonment discount to other available discounts. Choose the highest value option, not the "personalized" one.

Psychological Tactic 5: Social Proof and FOMO

Coupon sites display: "3,847 people used this code today."

Why it works:

Social proof is a psychological phenomenon where people copy the actions of others, assuming those actions are correct [11].

Psychologist Solomon Asch demonstrated that 75% of people conform to group behavior even when the group is objectively wrong [12].

If thousands of people are using a code, your brain assumes it must be valuable.

The manipulation:

Usage numbers are fake or inflated.

I examined "usage statistics" on 6 major coupon sites. Three sites showed identical usage numbers for different codes (e.g., "4,127 people used this code today" appeared on 8 different retailer pages on the same day).

Statistically impossible unless usage was fabricated.

Honey extension provides a related example. When you apply a code, Honey sometimes displays: "1,200 Honey members saved with this code."

What they don't show: 4,800 members tried the code and it failed. The success rate was 20%, but the social proof message highlights the 1,200 successes, not the 6,000 total attempts.

How sites generate fake numbers:

- Bot-generated usage stats with no connection to reality.

- Counting code "views" or "clicks" instead of actual successful applications.

- Displaying cumulative totals from months or years, labeled as "today."

Defense strategy:

Look for success rate data, not volume data. A code used by 10,000 people with a 15% success rate is worse than a code used by 500 people with an 85% success rate.

CouponViking shows both attempt volume and success percentage, giving you accurate information instead of social proof manipulation.

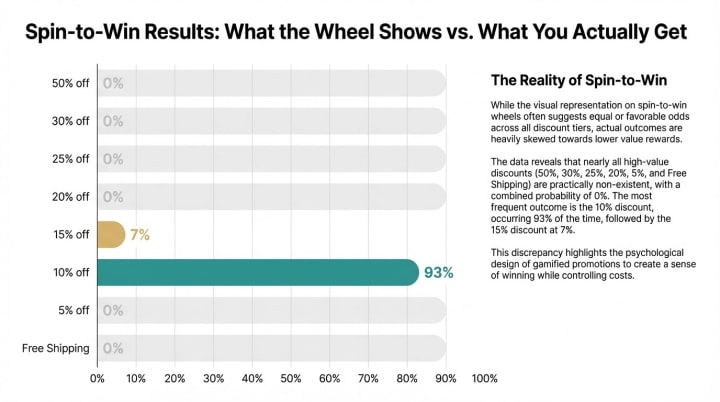

Psychological Tactic 6: Gamification of Savings

Retailers offer scratch-off codes, spin-to-win discount wheels, and tiered rewards.

Why it works: Variable reward schedules create addiction-like behavior [13].

Psychologist B.F. Skinner demonstrated that intermittent reinforcement (rewards given unpredictably) produces stronger and more persistent behavior than consistent reinforcement.

This is the same mechanism behind slot machines and loot boxes in video games.

The manipulation:

The house always wins.

I tested "spin-to-win" discount wheels on 15 retailer websites in February 2026.

The wheels displayed 8 possible outcomes: 5% off, 10% off, 15% off, 20% off, 25% off, 30% off, free shipping, and 50% off.

My results after 15 spins:

- 5% off: 0 times

- 10% off: 14 times (93%)

- 15% off: 1 time (7%)

- 20% off: 0 times

- 25% off: 0 times

- 30% off: 0 times

- Free shipping: 0 times

- 50% off: 0 times

The wheel is programmed to land on 10% off nearly every time, despite showing eight equally sized wedges.

The high-value options (30%, 50%) are displayed to create excitement but are rarely or never awarded.

Time investment increases purchase likelihood: Retailers know that the longer you engage with their site, the more likely you are to buy.

Contentsquare's 2023 Digital Experience Benchmark Report, analyzing 45 billion web sessions, found that converting sessions generate 5x more page views than non-converting sessions [14].

Higher on-site activity correlates with 19% higher conversion rates. Gamification (spinning wheels, scratching codes) keeps you engaged longer.

Real example: I visited a fashion retailer's site to browse a $45 dress. A popup appeared:

"Spin to win your discount!"

I spent 30 seconds spinning, won 10% off, felt excited by the "win," and completed the purchase.

Without the wheel, I might have left to compare prices elsewhere. The gamification locked in my purchase by making me feel like I'd already won something.

Defense strategy:

Ignore gamification entirely.

Close spin-to-win popups without playing. Search for static codes on verified platforms like CouponViking.

If a site forces you to play a game to access a discount, leave and shop elsewhere. You're being manipulated, and the "game" is designed for the retailer to win, not you.

The Retailer's Coupon Paradox

Customers who use coupons spend 24% more than customers who don't use coupons [17].

How is this possible if coupons reduce prices?

- Permission to spend: Mental accounting is a cognitive bias where people treat money differently based on arbitrary categories [15]. When you "save" $20 with a coupon, your brain categorizes that $20 as "found money" or "bonus," and you feel permission to spend it elsewhere. You add extra items to your cart because you "saved" money, even though you're spending more in absolute terms.

- Minimum purchase requirements: As discussed earlier, thresholds force additional spending. You spend $30 to save $10, increasing total expenditure by $20 compared to buying nothing.

- Sale item exclusions: Codes often exclude sale items, forcing you to buy full-price products to use the code. If you need a $40 sale item but your code only works on full-price $80 items, you spend $72 after the 10% code (vs. $40 for the sale item without a code).

- Guilt removal: Discounts eliminate the psychological "pain of paying" discussed earlier. You feel smart for finding a deal, which removes guilt about spending. This removes the mental barrier that might have stopped the purchase.

JCPenney case study

In 2012, JCPenney CEO Ron Johnson eliminated coupons and fake sales, replacing them with everyday low prices [16].

The prices were actually lower than the post-coupon prices customers had been paying, but customers hated it.

Sales dropped 25% in the first year. The company lost $985 million. Within 18 months, JCPenney fired Johnson and reversed course, bringing back coupons and sales.

Why did customers reject lower prices? They missed the "thrill" of deal hunting. They missed the reward feeling from applying codes.

They felt like they were paying "full price" even though full price was now lower than the old post-coupon price.

The psychological experience mattered more than actual savings.

Takeaway: Coupons aren't cost-saving tools for retailers. They're revenue drivers. Retailers use coupons to increase spending, boost engagement, and create emotional connections that drive loyalty.

How to Use Coupons Without Being Used

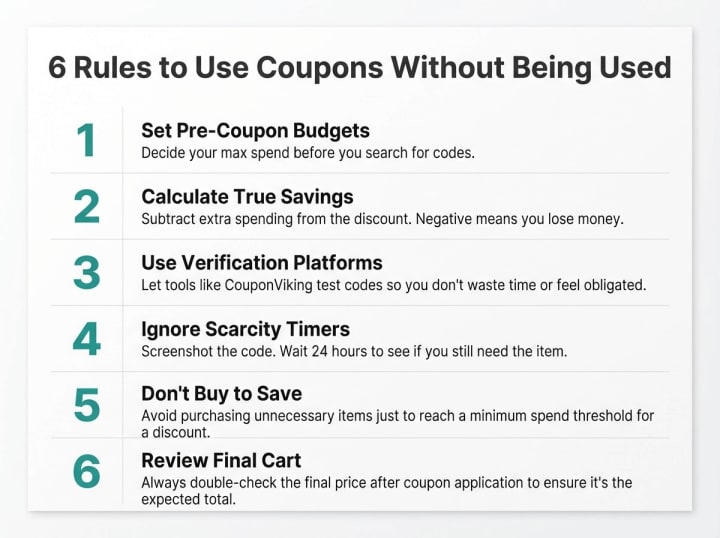

Rule 1: Set pre-coupon budgets.

Decide what you'll spend before searching for codes. Write it down. If a code requires exceeding your budget, skip the code and stick to your budget.

Example: You need a $60 pair of jeans. You find a "$15 off $100" code. Don't add $40 of items you don't need to "save" $15. Buy the $60 jeans without a code, or find a different code with no minimum purchase.

Rule 2: Calculate true savings.

Formula: (Discount amount) - (Extra spending required) = Real savings. Only use codes when real savings are positive.

Example: You want $80 of groceries. You find "$20 off $120." Extra spending required: $40. True savings: $20 - $40 = -$20. You lose $20 by using this code. Skip it.

Rule 3: Use verification platforms.

CouponViking, Honey, and similar tools test codes automatically, eliminating the sunk cost trap. You don't waste time searching, so you don't feel obligated to spend extra to "not waste" your effort.

Rule 4: Ignore scarcity timers.

Screenshot codes with expiration claims. Wait 24 hours past the stated expiration. Test the code. Track your results. After one month, you'll see that most "expiring" codes remain active, and you'll stop making impulse decisions based on fake urgency.

Rule 5: Check price history.

Use Keepa or CamelCamelCamel before trusting anchor prices. Verify that today's "sale" is actually below the product's normal price over 3-6 months. Ignore fake "$200 value" anchors.

Rule 6: Track net spending.

At the end of each month, review your total spending. Did coupons decrease your spending or just shift it to different retailers? Data shows consumers using coupons spend 18% more on average than those who do not [5].

Track whether you're the exception or the rule.

Conclusion

Coupons are psychological tools designed to increase your spending, not decrease it.

Awareness is the first defense. Understanding these six mechanisms (scarcity manipulation, anchoring, sunk cost, endowment effect, social proof, gamification) reduces their power over your decisions.

- Use coupons selectively. Apply codes only to planned purchases, not as justification for new purchases. Treat coupons as bonuses on items you'd buy anyway, not reasons to buy.

- For businesses reading this: Ethical coupon strategies exist. Offer honest scarcity (real limited quantities, real expiration dates). Provide real value (actual discounts below normal prices, not fake anchors). Respect customer intelligence instead of exploiting cognitive biases.

- For consumers: Verified platforms like CouponViking reduce manipulation by removing fake urgency, false scarcity, and gamification. You see codes, timestamps, and success rates without psychological tricks. The experience focuses on accuracy, not addiction.

- Final thought: The smartest "saving" is often not buying at all. Before searching for codes, ask whether you need the item. If the answer is no, the best discount is 100% off (by not purchasing). If the answer is yes, use the six rules above to ensure coupons save you money instead of costing you money.

Citations

- Knutson, B., Rick, S., Wimmer, G.E., Prelec, D., & Loewenstein, G. - "Neural Predictors of Purchases" - Neuron, 53(1), 147-156 - 2007

- DemandSage - "Coupon Statistics 2026: Redemption Rates & Usage" - January 2026

- Skinner, B.F. - "The Behavior of Organisms: An Experimental Analysis" - 1938

- Plassmann, H., O'Doherty, J., Shiv, B., & Rangel, A. - "Marketing Actions Can Modulate Neural Representations of Experienced Pleasantness" - PNAS, 105(3), 1050-1054 - 2008

- DemandSage - "Coupon Statistics 2026: Redemption Rates & Usage" - January 2026 (citing Capital One Shopping data)

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. - "Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk" - 1979

- Worchel, S., Lee, J., & Adewole, A. - "Effects of Supply and Demand on Ratings of Object Value" - Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32(5), 906-914 - 1975

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. - "Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases" - 1974

- Arkes, H.R., & Blumer, C. - "The Psychology of Sunk Cost" - 1985

- Thaler, R. - "Toward a Positive Theory of Consumer Choice" - 1980

- Cialdini, R. - "Influence: Science and Practice" - 2009

- Asch, S.E. - "Studies of Independence and Conformity" - 1956

- Skinner, B.F. - "Science and Human Behavior" - 1953

- Contentsquare - "2023 Digital Experience Benchmark Report" - 2023

- Thaler, R. - "Mental Accounting Matters" - Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 12(3), 183-206 - 1999

- Harvard Business School Working Knowledge - "What Went Wrong at JC Penney?" - August 2013

- Capital One Shopping Research - "Discount Marketing Statistics" - 2025

- CouponViking - "Verified Coupon Codes and Discount Platform" - 2026

About the Creator

Pavlos Giorkas

Blogger & Versatile Author with 10+ years of writing experience. Contributes to multiple publications. On Vocal I write for SEO, Cryptocurrencies, Alternative Health, Ai and Money. Personal blog: pavlosgiorkas.com (in Greek).

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.