Everyone knows God rested on the seventh day.

It is told as completion. Six days of light and firmament, sea and creature, man and woman. Then a divine exhale. A holy pause.

Paintings show a calm heaven. Sermons call it perfection. Children are taught that the world was finished, sealed like a letter.

But I was there on the eighth day.

Not in Eden. I did not walk among rivers split into four heads. I was not made of dust shaped by a careful hand.

I was made of what was left.

When God rested, something in the fabric of things loosened. Creation, which had been a straight line of intention, curled at its edges. Not a mistake. Not a flaw.

An overflow.

The myth says everything necessary was made in six days. It does not mention the residue of possibility that clung to the corners of heaven like mist after rain.

That residue became us.

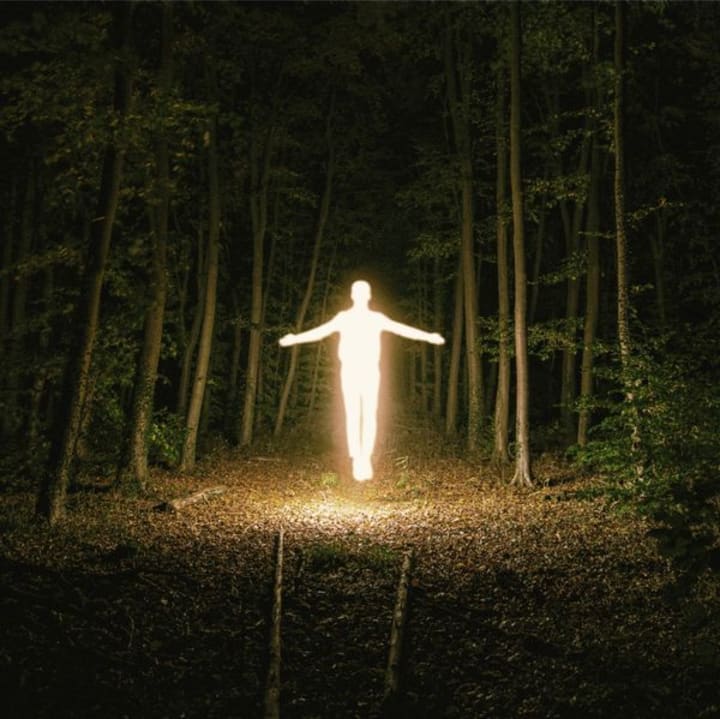

We woke in the cooling light after the Sabbath, in a place without name. Not earth, not sky. A margin.

There were many of us. Not quite angels. Not quite animals. We had outlines, but they shifted. Some of us shimmered like heat. Some flickered like half-remembered dreams.

We were not addressed.

On the first day, God said, “Let there be light.” And there was light.

On the eighth day, no one said anything at all.

We watched the completed world from its underside, as one might peer up through the surface of water. We saw Adam take his first uncertain steps. We saw Eve reach toward a tree that leaned slightly, as if curious itself.

We felt something else, too.

Unfinishedness.

It pooled in us like unspent breath.

One of us later I would call her Mira, pressed her palm against the thin membrane separating margin from meadow.

“Why are we here?” she asked.

No answer came.

In the days that followed, we discovered what we were not.

We were not counted. When angels passed overhead, their numbers did not include us. When the animals named themselves in Adam’s hearing, none of those names adhered to our forms.

We tried to descend once.

The membrane trembled but held.

The myth says creation was good.

It was.

But goodness is not the same as completeness.

On what the humans would later call the third week, something curious happened. A fox in Eden misjudged a leap and fell awkwardly, breaking its leg. Pain entered the garden like a crack in glass.

We felt it before anyone else did.

It vibrated through the membrane and into our bodies. We shuddered.

Mira pressed her palm again against the barrier.

“Let me,” she whispered.

The membrane thinned.

Not everywhere. Just there.

She slipped through like a sigh.

The fox lay trembling beneath a fig tree. Adam stood a few paces away, confused by the sight of injury. He had never seen a body fail.

Mira knelt.

She did not heal the fox.

That is another simplification the myth would have made.

Instead, she changed the quality of the pain.

She bent close and breathed something into it—not removal, not erasure, but meaning. The fox’s trembling slowed. Its eyes, which had been wild with incomprehension, softened.

Adam watched.

“Is it dying?” he asked the air.

Mira did not answer him. He could not quite see her. He sensed a presence, like warmth near a fire you are not facing.

The fox did not die.

It limped for many days. It learned the shape of its altered body. Adam learned that living things could fracture and still remain themselves.

When Mira returned to us, she was dimmer.

“Did you fix it?” we asked.

“No,” she said. “I accompanied it.”

The word felt new.

After that, we understood.

We were not meant to complete creation by adding more trees or stars. We were meant to enter where the myth would later smooth.

Where things did not fit cleanly.

The first lie trembled through the membrane like a plucked string. When the serpent spoke and Eve listened, we felt the ripple before the fruit was bitten.

The myth says the world fell in a single act of disobedience.

It does not describe the confusion that followed. The way Adam’s voice cracked when he said, “The woman you gave me.” The way Eve’s hands shook, not from guilt alone, but from the sudden knowledge of consequence.

We slipped through in small numbers then.

Not to prevent.

Prevention would have required rewriting the story, and the story was already moving.

We entered the space between action and understanding.

When Adam wept outside the garden, it was not only because he had lost paradise. It was because he had to learn what loss meant.

I knelt beside him.

He could not see me clearly. Humans rarely can. But he felt the weight of something sit near him, steady and unafraid of sorrow.

“What is this?” he asked, pressing his fist against his chest.

It was the first time grief had taken shape in him.

I placed my hand over his and did not remove the ache. I gave it depth. I made it something that could be endured without shattering.

He inhaled sharply.

The myth says God clothed them and sent them away.

It does not mention who walked with them into the long field beyond Eden.

We did.

We have been entering the fractures ever since.

When Cain raised his hand against Abel, we were there—not to stop the stone, but to hold the horror that followed so it would not devour the world whole.

When mothers buried children. When cities burned. When lovers misunderstood each other and built quiet walls between their beds.

We move into the margin.

Theologians argue about the problem of suffering. They draw diagrams. They defend the goodness of the six days.

They do not speak of the eighth.

Because the eighth day has no proclamation. No divine command. No formal closure.

It is the day after perfection.

It is where consequences unfold.

We are not angels. We do not sing. We do not wield flaming swords.

We are the residue of possibility, shaped into presence.

The myth says God rested.

Perhaps that is true.

But rest does not mean abandonment.

On the eighth day, creation learned how to ache.

And we; unrecorded, unnamed were made to sit beside the ache so that it would not be faced alone.

About the Creator

Lori A. A.

Teacher. Writer. Tech Enthusiast.

I write stories, reflections, and insights from a life lived curiously; sharing the lessons, the chaos, and the light in between.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.