Written by James D. Merrick, January, 19, 2021

In high spirits, my Juan and I departed early that fourth of July morning from our Bakersfield home. We were headed for a family reunion in Redlands. The weather person had forecast a sunny clear-sky day for all of California. That morning, while I put on my sport shirt, the anticipation switch in my brain clicked into fast forward. My fingers fumbled with the buttons as the good kind of jitters circulated inside of me. I knew from past gatherings that being with family members would fill me with good vibes, bad jokes, and scrumptious food. The thought of being immersed in a pool of hugs, handshakes, and kisses made me pay special attention to my reflection in the bathroom mirror: I wanted to look my best. I beamed at the thought of socializing with seldom-seen members of my clan and especially my former wife, Nancy. But the die was cast: no one, not even she, suspected the devastation already taking place inside her body.

A bounty of home-cooked food smothered the buffet tabletop at the scheduled three p.m. dining hour. With its heady aromas, the epicurean display of culinary art lured the family members into the dining area of my daughter, Kim’s, home. Turmeric, sage, and cinnamon graced the air. Pockets of laughter filtered through the animated conversations while guests hovered about the food, eyeing their favorite holiday delights. We were waiting for Nancy. She didn’t arrive. At three-thirty, Kim asked her guests to go ahead and eat. Each filled a plate from the sideboard and settled down around the lengthy dinning table or scattered on upholstered chairs around the living room.

Nancy was a great communicator. Not hearing from her was troubling. I was sure something unpleasant had happened. Concern for her welfare cut short my appetite. I set aside my empty plate and sat beside Juan to wait. Other family members chatted in a knot around the kitchen bar or sat on sofas in the T.V. room. Their voices muted as concern for Nancy penetrated their conversations. In an attempt to lift the mood, Kim made the rounds taking drink orders and prompting folks to help themselves to seconds. Nancy hadn’t arrived by four…or five… or six p.m.

At 8:00 p.m., I called Nancy’s life-partner, Ron, who lived separately from her in Tehachapi. With an edge of alarm in my voice, I told him she hadn’t arrived. He explained that she had planned to drive her seventy-nine-year-old self to the gathering without him. He had a previous commitment with his grown son and hadn’t planned to accompany her. He wasn’t aware of the time she left her house in Bakersfield or the route she intended to take. Wanting to assess blame, I thought, Why didn’t he know her plans? Accusing myself, Why didn’t I know? If I had known she planned to travel alone, I would have asked her to ride with Juan and me. Nancy’s hatchback had a GPS, but I didn’t think she knew how to use it. In a panicky attempt find her, Kim reached out for assistance and called a policeman friend who volunteered to check accident and crime reports.

At 9:00 p.m., Nancy breezed into the living room, a vision in pink, adorned in smiles and sparkling with self-confidence. As if nothing had happened. she greeted the sea of drawn faces with hugs and kisses and the gentle admonition, “You shouldn’t have worried.” According to her, she took a wrong turn and eventually asked a mail delivery person for directions. I thought her version was full of holes. As far as I could tell, she drove Interstate 15 north to Barstow, instead of Interstate 15 south, which eventually brought her to us that night in Redlands. Flashing through my thoughts were the unanswered questions: Why didn’t she use her cell to call one of us? Why didn’t she stop at a gas station to ask for directions or get a map?

Nothing more was said until a month later, when she disappeared. Ron last saw her following behind him in her car as he drove from Bakersfield to Tehachapi. She didn’t arrive at his place. He sent out the alarm to family members and contacted the California Highway Patrol and local police departments. I began calling emergency rooms at local hospitals. Nothing. Images of her torn and twisted body cursed my night. I waited the hours, cell in hand, wanting its inevitable ring. It came at sunrise. Nancy was found in an all-night MacDonald’s, twenty miles away. She evidently spent the night chatting with customers while waiting “for her boyfriend to meet her.” Two policemen took her home in a patrol car. The official police report indicated she suffered from memory loss. Based on that document, the California Department of Motor Vehicles revoked her driver’s license. Nancy was officially unable to drive.

Within days, Ron and I took her to the family physician who conducted blood and memory tests and referred Nancy to a neuropsychologist for tests of her ability to think and solve problems. The final diagnosis was “Probable Alzheimer’s Dementia.” My brain went numb. It was flooded with memories of when her mother was institutionalized at age fifty-five with the same condition. Nancy’s mother had dwindled away for five years in a long-term care facility. Alone and discarded, she remained human refuse until her death.

Willing to try anything that might help her mother, Kim made the decision to let Nancy remain at home in Bakersfield, surrounded by familiar objects that might guard her memory. Kim became estate manager and supervised her mother’s care from Redlands, four hours away by car. Nancy’s basic income came from our divorce settlement. In reserve, were her savings and the equity in her house. On the weekends, Ron kept her with him in Tehachapi. I volunteered to be with her the four remaining weekday mornings. Kim hired a part time caregiver for weekday afternoons. Additional financial assistance came our children and from family friends.

Little by little, Nancy’s world became too problematic for her to be unsupervised during any daytime hours. As her ability to think deteriorated, unsafe things happened. She began to ride her bicycle across a busy highway to the nearby supermarket. Pots and pans were left on the stove to char. The bathroom faucet was left running at night, allowing the water to overflow and flood her bedroom. The iron remained on and the water in her garden hose continued to flow. On cold nights and hot days, she was unable to adjust the thermostat.

As a stop-gap measure to postpone the foreseeable need for twenty-four hour care, Kim implemented ways to reduce the probability of danger. Because caregivers brought Nancy’s meals, the electric stove was not needed and was disconnected. Only the microwave and the electric coffee pot remained operable. Nancy no longer needed to press clothing--the iron was put away. The heating and air-conditioning controls were changed to simple on-off settings. The water was turned off during the night. Those changes resolved most of the problems at that time, but not all. Nancy was still unsupervised four nights a week. As an added security measure, Kim installed surveillance cameras inside the house. If Nancy left her bedroom during the night, which she seldom did, a cell phone alarm alerted Kim. She was then able to watch Nancy on her cell and call for help if necessary (Fortunately, this never had to happen.).

In the beginning of my caregiving with Nancy, she punctuated the time with frequent complaints about the loss of her driver’s license: “I never got a ticket in all my life. I’m a very good driver. I’m going to drive anyway!” The loss of her license was an everyday theme in her conversation. She was angry and argumentative about it. I’d never known her to carry on like that about anything, but there was little I could say to distract her from her monologue. When I repeated the events that caused the loss of her license. She denied having been at MacDonald’s and created her own scenario: “Ron drove off without me. I pulled to the side of the road to wait for him.” Until the day her car was sold and out of her life, anger flowed out of her in bitter words of protest: “I never got a ticket in all my life. Why won’t they let me drive?”

I wanted my time with Nancy to be filled with visual stimulation to help keep her brain active. Each time I visited, we went to a nearby Starbucks to drink coffee and look at photos and videos on my tablet. We also talked about the passing traffic. Nancy had been an artist for most of her life and was attracted to the various colors of vehicle paint and the lifelike displays of fruits and vegetables affixed to side panels of passing trucks. She called out, “Look at the blue!” or “What beautiful fruit!” Our other routine at Starbucks was to look at family photos, Facebook posts, and YouTube animal videos. We sat shoulder to shoulder and talked about what we saw. Sometimes, a “regular” would stop by our table and greet us. Whenever asked, “How are you, Nancy?” She, straightened her back against the chair, spread her lips into a broad smile, and said, “Life is wonderful! I have a wonderful life!”

After thirty minutes with the tablet, we usually headed out to run errands. Mostly, we shopped for groceries, did the banking, and browsed at the Goodwill and Salvation Army stores. When Nancy wandered around thrift stores, her face became very serious. She held up articles of clothing and stared at them with the look of a quality-control expert. It pleased me to watch her at the shelves of toys. But moisture collected in the corners of my eyes whenever she clutched a floppy-eared rabbit or a soft brown bear to her breast. She drew their fluff across her cheek and smiled down upon them. Her childlike squeal punctuated the air. Before leaving a thrift shop, Nancy loaded her arms with stuffed animals and waited her turn quietly in line to pay. We counted out her money at the cash register. She took her treasures home to save for the Christmas Toys-for-Tots drive. All too soon, a forgotten event.

Some mornings, we toured the neighborhood to look at homes and comment about the changes done to yards. From time to time, we drove to Lowe’s nursery to look at plants. Nancy treated plants as though they were good friends, oohing and aahing about the colors and shapes of flowers. She was in her fifth year of Alzheimer’s the last time we went there. When I arrived at her house, I unlocked the carport door to let myself inside. The house was still dark. I flipped the light switch in the kitchen, then the switch in the TV room. The table clock marked eight a.m. I made my way down the hallway to her bedroom door and knocked. No answer. Another knock. No voice. I opened the door a crack to peer inside. She sat on the edge of her bed. Her pink flannel nightgown was pushed down to her waist. One strap of her frappe brassiere hung twisted from her right shoulder. Her feet in white stockings protruded from below black dress pants and supported her hunched body at the edge of the mattress. Like a trapped mouse, she leaned forward, hands in her lap and sat motionless, waiting silently.

“Can I help you get dressed?” “Humm. I don’t know.” She remained there, immobile and bewildered. I entered and helped her remove the nightgown, rearrange the straps on her brassiere, and pull on a blue and black polyester blouse.

She made her way into the T.V. room, sat on the couch, and slipped her feet into her waiting white walking shoes. She remembered how to fasten the Velcro and bent down and tightened the straps. I helped her insert her arms into the sleeves of her turquoise fleece jacket, anchored the zipper into position and raised the slider to her neck. “Thank you,” she said, automatically, as she reached for her nearby pink belly-bag. I wrapped the belt around her waist and clicked the buckle into place, something she could no longer do.

When we arrived at the carport door, she turned and automatically checked the back-door latch to make sure that door was locked. She opened the door to the carport, stepped outside, and turned the latch to the right. As I exited, I turned the latch the correct way, to the left, and locked the door.

Lowe’s was only fifteen minutes away by car. On the way to the parking lot, I slowed in front of a store selling unfinished furniture. The yard display was one of Nancy’s favorites. Dozens of life-size animal carvings lined the chain-link fence: American eagles, brown bears, geese, ducks, and tortoises. As we passed, Nancy’s head snapped around. She gazed at the display, “Oh, my! I love those animals!”

Early in the morning, it was easy to park close to the entrance of Lowe’s garden area. As we walked toward the exterior displays of flowering plants, Nancy was drawn to hanging baskets of purple petunias, “Look at that! It’s beautiful!” She scurried to the nearby table of red begonias and ran a fingertip gently across the petals and along a leaf. Her face was relaxed. Her brown eyes showed a glimmer of recall. We drifted through the entrance gateway and into the main display area. Heady fragrances traveled through the air to greet us. A promised land of plants carpeted the area in a blaze of crayon colors as far as we could see. We meandered down each aisle, being careful to avoid the black rubber water hoses zigzagging across the concrete floor and the puddles of accumulated water. As we proceeded, Nancy pivoted to the right, then to the left, then scurried down aisles here and there. A smile anchored on her face. Her eyes became childlike as though in wonder.

Near the end of our visit, I asked her to choose a plant to take home to her garden. “Oh! That would be nice,” accompanied the hand that rose to her lips as she twisted around and around to make a selection. I reminded her of the purple petunias. She took one home.

At Nancy’s place, I helped her choose a terracotta pot from the previous year’s stockpile. She yanked the weeds from the hardened potting soil. I helped her add new potting mix and reminded her how to use an old spoon to form a depression for the new plant. The root ball was inserted into the loose soil. With fingers that still knew, Nancy tamped the mix firmly around the roots. I placed the pot on a flat stone directly in front of the kitchen window and took her hand as we stepped back to admire our work. She turned on the hose and dragged it to the pot. Water trickled into it without flushing out the soil. I followed her into the house and over to the kitchen sink where she leaned forward and peered outside. Her hands braced on the countertop. Her eyes focused on the single purple blossom centered in the terracotta pot with its pistil aimed at the morning sun. Her hands laced together on her chest, her eyes became brilliant, “So beautiful!” she said.

*****

Nancy never seemed to be aware of her condition. In the beginning of the disease, she was able to communicate by phone. Her sister, Loretta, called monthly from Colorado and sent holiday greeting cards with updates about her life. Our son, Ty, called from Puerto Rico every three or four weeks. In between times, he wrote her long letters. Son Brad phoned her from Texas from time to time and sent candied nuts and a family photograph each year. Son Todd and his wife, Jan, sent a box of fruit from Colorado at Christmas time and made frequent check-up calls to Kim. They used Facebook to inquire about Nancy’s welfare. Kim called her mother every night.

As the disease progressed, Nancy stopped riding her bike or caring for her garden. She lost the ability to communicate over the phone and to write letters. She forgot she was a lifelong artist and was unable to recognize her paintings. She lost the ability to follow a storyline in conversation or on television. Eventually, she spoke only when spoken to. Kim continued to call, but the other calls stopped coming. I ached as I watched Nancy lose contact with her children, loved ones she devoted her life to nurture. As for myself, I accepted her decline into darkness as an event beyond my control. Even though I ached at losing her, she seemed to approach the end of life in peace.

*****

My last day as Nancy’s caregiver came on March 31, 2020. Covid-19 was sweeping the nation. The state was in lockdown. As the virus cut pathways of death across the world, the various caregivers coming and going in Nancy’s life became potential carriers for its spread and a threat to the safety of each of us. I was immersed in fear of becoming infected. I made the decision to remain at home with Juan in self-imposed isolation to reduce our exposure to the deadly virus. Other caregivers took my place. A feeling of numbness joined me on my way to Nancy’s house that last morning together. People were dying everywhere. Hospitals overflowed with Covid victims. I wondered if this might be the last day I would ever see her. I thought about the thirty-eight years she and I had shared as husband and wife, the four children we had raised, the unique places we had lived, the remarkable things we had done together, and my homosexuality that ended our marriage. A single tear caught in the corner of my eye and hung there, as if waiting to be wiped away. I wanted that morning to be one of Nancy’s good ones, a morning when she was able to get out of bed and dress herself. In my mind’s eye, I could imagine her getting ready for the day:

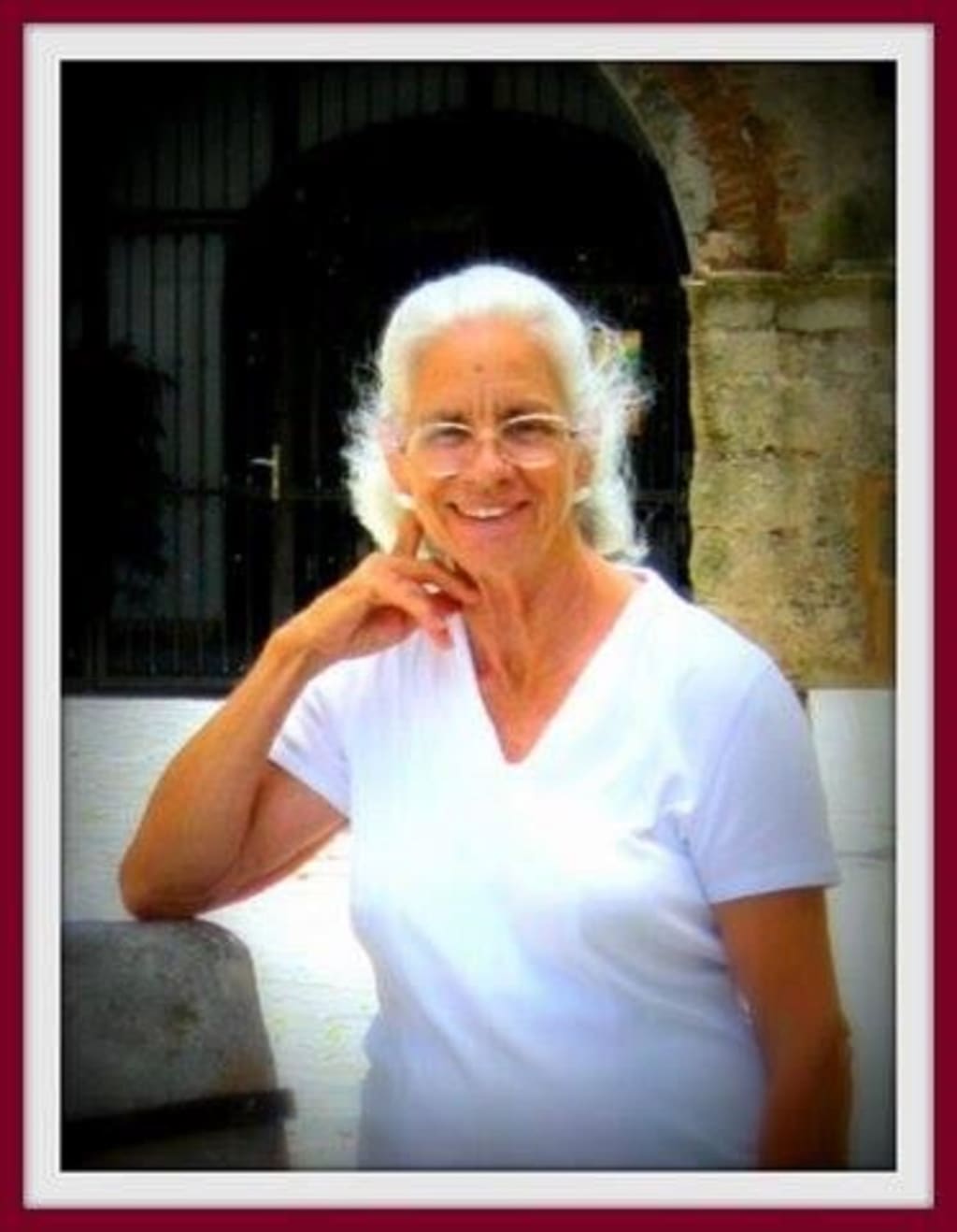

She will wake wearing her pink-flowered flannel night gown and white anklets and will move into the bathroom where she will turn on the light. She will look into the mirror and use her slender fingers to comb her long white hair away from her face and back over her shoulders. A handful of silver-gray at the back of her head will be grasped and wrapped too loosely into a pony tail with an elastic band. Instead of hanging down the back of her head, it will drape comically over one ear.

After stepping into her pink grass-stained house slippers she will make her way down the hallway to the dark family room and flip on the light switch. No longer will she recognize the art work that surrounds her or the photos of her children on the desk. She will shuffle through the room on her way to the kitchen and open the cupboard where dishes are kept. A white and blue porcelain teacup will be placed on the white tile counter top into which she will pour cold water from the plastic bottle. A teaspoon from the storage drawer under the counter will be used to add instant coffee. The cold water will be stirred. She will push the cup of coffee to the back of the counter, rinse and wipe dry the spoon and return it to the drawer.

She will then walk to the carport door, open it, and in her night clothes she will cross the concrete to the dew-covered front yard. As she has done many mornings, she will make her way across the wet grass to the far corner of the house, glance toward the fenced storage area, stare up at the neighbor’s dying tree, and return across the grass to the carport to reenter the house. She will lock the door behind her and move to the cup of cold coffee on the counter, which she will place inside the nearby microwave. The start button, marked with red tape, will be pushed. The oven will begin its mechanical purr.

Forgetting the coffee, she will return to the family room and locate the remote for the TV. “On” will be pushed. Channel twenty-nine, “Let’s Make a Deal” will flutter into focus and blare into the room. “Volume” will remain at maximum. Next, she will move to the couch, sit on the fallen backrest pillow, and stare at the images on the screen.

When I enter through the carport door at eight this morning, she won’t recognize me or be afraid. I may see a reflection in her eyes, a trace of the sparkle that was once there. Her lips may part as if they are about to form a smile or tell me something. When I hug her and say: “Good morning, Nancy Merrick. I love you,” she will cling to me for the longest time.

*****

I saw Nancy one more time. My journal records that event:

Saturday, June 28, 2020. I have a lot to write about today. Kim’s here with Nancy this weekend in Bakersfield. She’s making preparations to move her mother into long-term care near Redlands. Nancy no longer recognizes either of us or her surroundings. That morning she remained inside on the couch, staring at the T.V. I know the time has come.

Kim and I sat outside in the cool on two cast-away chairs bought one day to be reupholstered. Sadness draped our conversation and brought it to a close prematurely. I ran out of things to say and the desire to say more. As I stood to leave, Kim asked if I would like to come inside to greet Nancy. We entered the house and walked to the T.V. area. She was seated with her back to me. Her long white hair no longer draped down the rear of the sofa, it had been cut to shoulder length. As I moved toward her, she continued staring in the direction of the television. There were no indications in her behavior that she understood the voices coming from the flashing screen. I stood in front of her and blocked her line of vision. As she glanced up, her distant gaze turned away from the program and passed through me. Her lips remained sealed; her face a coverless book.

As I prepared to say “Good-buy,” the dread of losing her churned within me. I reached out and held the fingertips of her left hand. Smiling gently, my lips trembled. I said, “Hello, Nancy.” No response. I lowered her hand, aware of the remorse settling in my bones, and stepped away. Her stare followed me, unblinking. In a silent goodbye, I raised my hand, fingers together in a blade, and gave it a gentle wave. With the faintest of smiles, she raised hers, like Queen Elizabeth, and waved back.

About the Creator

James Dale Merrick

I have had a rich, and remarkable life. Sharing my adventures brings me joy.. I write about lots of things. I tell about building a home in the rainforest, becoming a life model, love, death, grief, and retiring. Please join me.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.