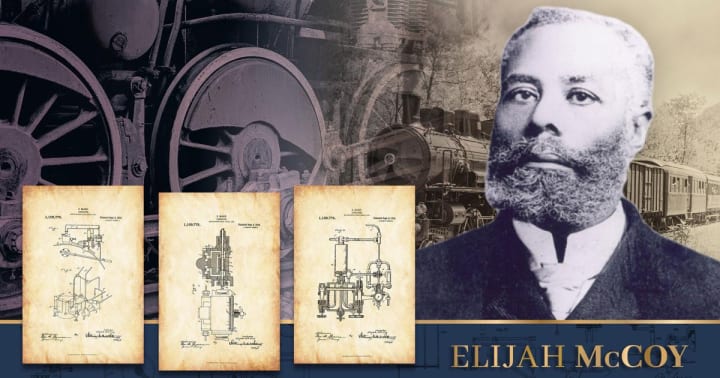

The Real McCoy

How One Inventor’s Railroad Breakthrough Kept America Moving

Byline: LEAVIE SCOTT

Dateline: February 19, 2026

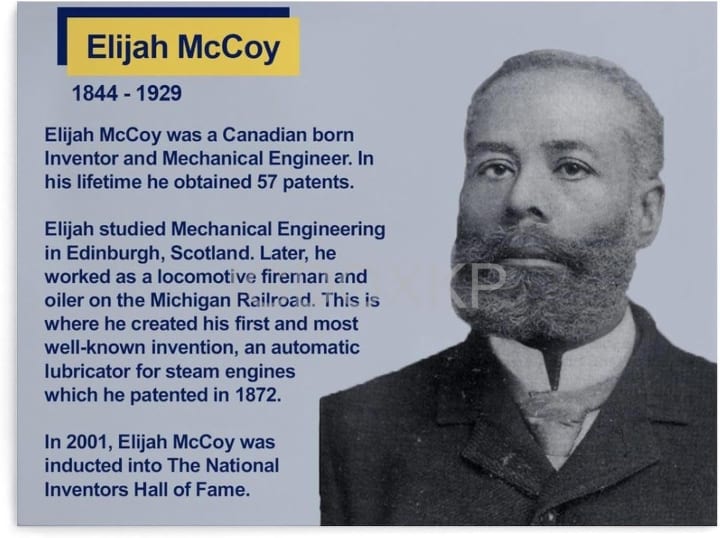

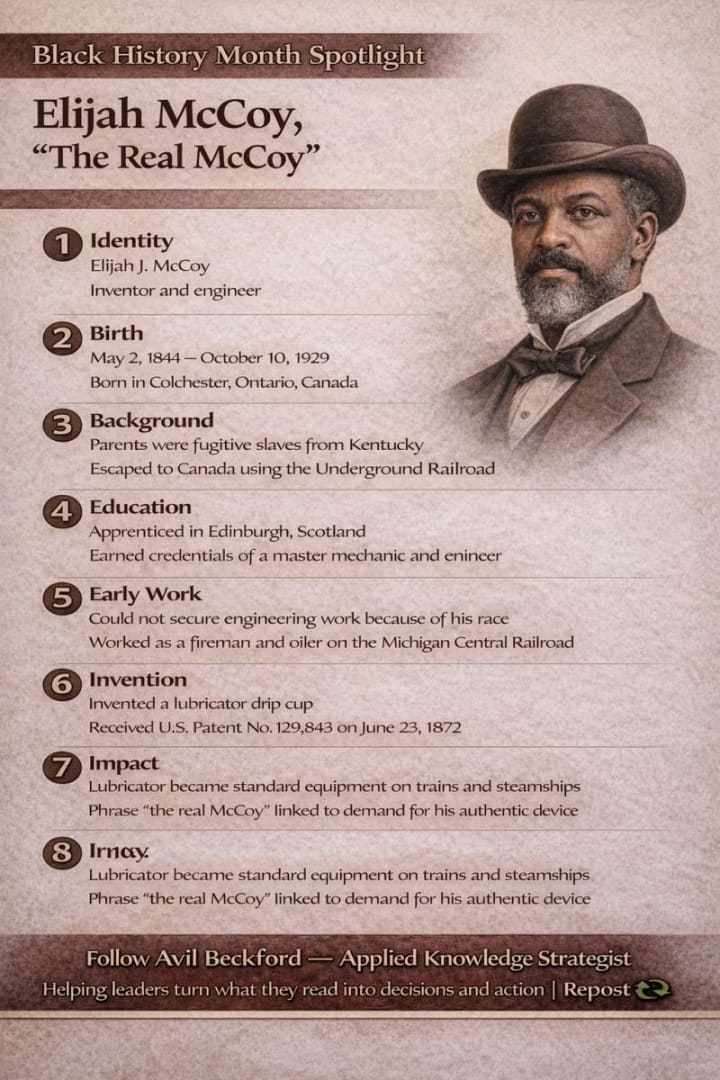

In the grand narrative of American innovation, certain names ring out like the steady cadence of a piston—powerful, rhythmic, indispensable. Elijah McCoy (1844–1929) is one of those names. His story travels the full length of a railroad line, from the distant signal of hope to the hard work of arriving at a destination. Born to parents who found freedom through the Underground Railroad and trained as a mechanical engineer in Scotland, McCoy returned to a United States still shackled by prejudice. Barred from opportunities his education should have guaranteed, he took a job as a railroad fireman—feeding the engine, monitoring gauges, and, crucially, oiling the moving parts that made those iron horses run.

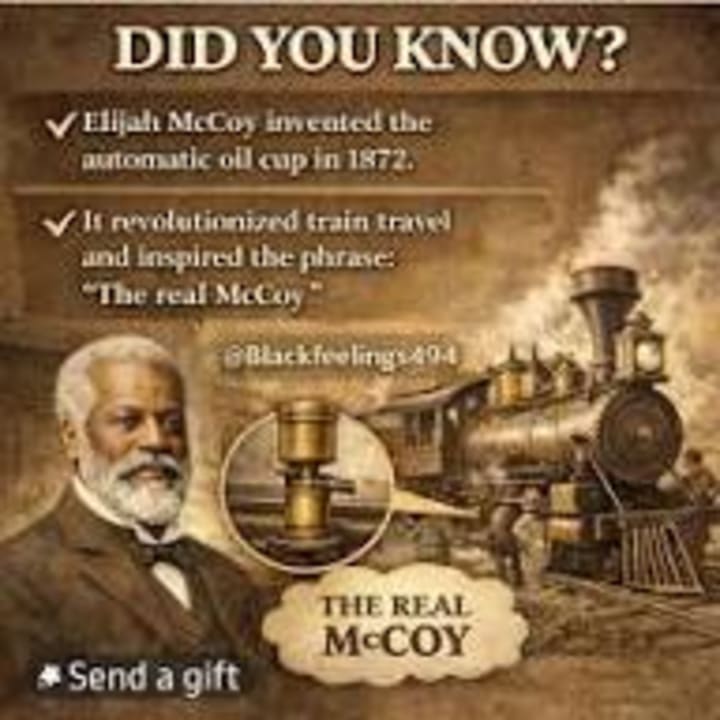

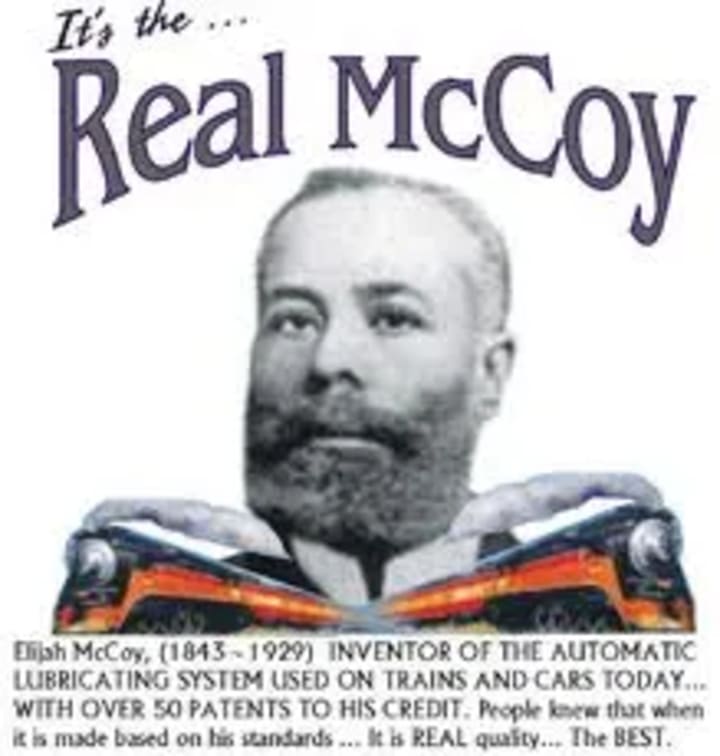

What followed was a feat of clarity and courage that would redefine industrial reliability: an automatic lubricating device that kept engines moving without constant shutdowns. It worked so well, in fact, that folklore and industry alike came to seek “the real McCoy”—not a cheap imitation, but the device that could be trusted to keep trains on schedule and commerce in motion.

This is not just a tale of clever mechanics. It’s a newsworthy profile of perseverance—of an engineer who saw a problem every day on the job and built a solution so effective it became idiom. And in an era where supply chains, efficiency, and safety remain front-page concerns, McCoy’s legacy feels as current as the next freight timetable.

From Flight to Forge: A Family’s Start in Freedom

Elijah McCoy’s parents fled enslavement in the American South, moving northward along secret routes maintained by a coalition of abolitionists, faith leaders, and everyday risk-takers committed to one radical idea: the dignity and liberty of every person. They reached Canada, where Elijah was born. Freedom did not confer wealth, but it did offer possibility—and the McCoys invested heavily in their son’s potential.

As a teenager, Elijah crossed the Atlantic to study in Edinburgh, Scotland, at a time when American training pipelines were largely closed to Black students. The curriculum was rigorous: thermodynamics, metallurgy, drafting, and applied mechanics. The Scottish workshops fostered both a respect for precision and a habit of pragmatic problem-solving. He learned to know a machine by the feel of it—what a rhythmic clatter might tell you about a bearing, or how shine and smell can reveal oil breakdown from heat.

Armed with credentials and technical acumen, McCoy did what any young engineer would do: he went home looking for a job. But the rails were crooked; discrimination turned technical interviews into non-starters. In one of the quiet injustices of the era, a trained engineer was offered labor that required muscle over mind.

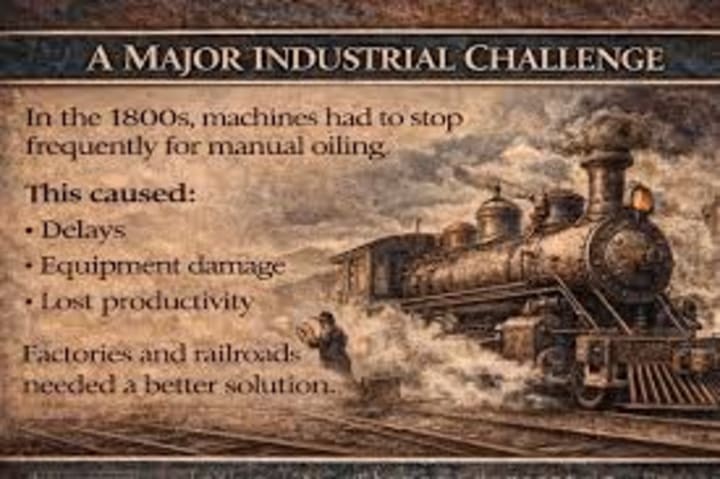

The Fireman’s Eye: Problem-Solving in the Heat of the Cab

As a railroad fireman, McCoy worked from the furnace door out to the last axle. Coal and kindling kept steam pressure up, but motion was all about lubrication. In the 19th century, locomotives and industrial machines needed frequent stops so workers could oil bearings, rods, and other moving assemblies. Without lubrication, friction would spike, metal would heat and expand, and—if you pushed your luck—something would seize or snap. These stops were a costly ritual: time lost, schedules blown, money squandered.

McCoy’s vantage point was perfect. He watched the needle on the pressure gauge, the color of the smoke, the shimmer where metal met metal. He asked a straightforward question with far-reaching implications: Why must we stop to oil at all? Why can’t the oil flow while the machine runs?

The answer emerged not from a single brainstorm but from dozens of small insights earned over hot shifts and colder nights at the workbench. Oil must be metered consistently. It must reach precisely the right surfaces—even when gravity and speed conspire against it. It must be robust enough to withstand vibration, heat, and grime. And the system must be simple enough for a railroad crew to trust and maintain.

The Lubricating Cup: A Small Device with a Giant Wake

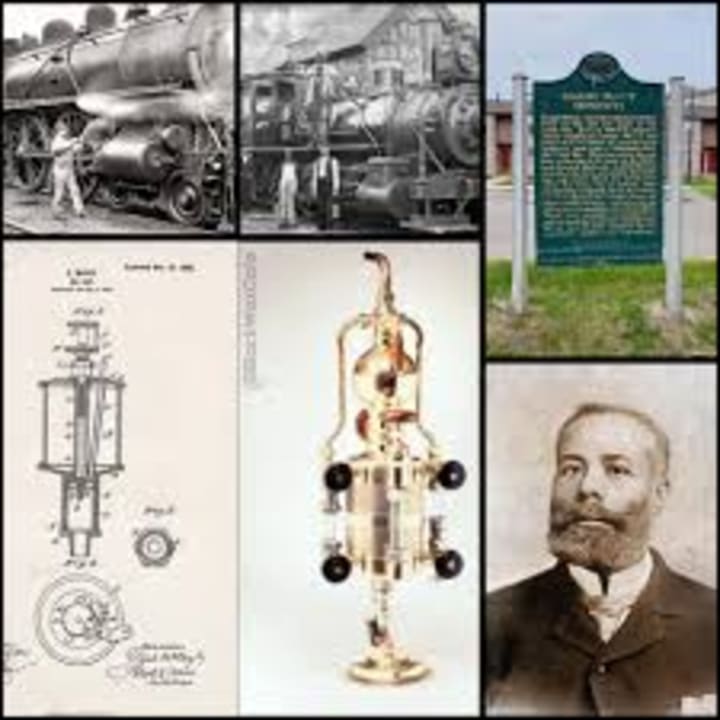

McCoy’s solution was an automatic lubricator—often called the lubricating cup or drip cup—that delivered oil to critical parts of an engine while in continuous operation. The genius lay in controlled flow: gravity-fed and pressure-assisted designs that seeped oil at a predictable rate, through channels and valves that wouldn’t clog easily. Some models used sight-feed indicators—glass compartments where operators could literally see the oil dripping—offering both peace of mind and a quick check for adjustments.

This changed everything for railroad operations. Instead of pausing to hand-oil bearings at regular intervals, engineers could run farther and faster with less risk of overheating. Bearings ran cooler, wear decreased, fuel efficiency improved, and schedules suddenly looked more like promises than hopes. Workers remained safer because fewer emergency stops meant fewer rushed procedures around hot, moving machinery. The device was remarkably compact, but its effects rippled outward through the economy: more reliable trains meant more reliable shipments, and more reliable shipments meant smoother business.

Industrial managers and locomotive crews developed a preference: if it was a McCoy, they wanted it. Whether or not the phrase “the real McCoy” was born precisely from these purchasing decisions, the cultural association became enduring shorthand—“Give me the genuine device, the trustworthy kind, the proven solution.” The phrase leapt from depots to parlors to print, a testament to the reputation of a product that fused elegant design with tireless dependability.

Iteration, Patents, and the Quiet Grind of Innovation

McCoy did not stop at a single design. He refined flow mechanisms, improved seals, and found ways to adapt the device for different machines—locomotives, maritime engines, and factory equipment. When a design proved itself in the field, McCoy worked to lock in the learning, filing patents that captured the cleverness and protected the market incentive to manufacture quality units. His portfolio would grow to dozens of patents over a long career.

This iterative discipline is familiar to any modern engineer: observe failures, isolate variables, test countermeasures, and reduce the unknowns. McCoy’s shop became a feedback loop where the network of rail workers and foremen indirectly contributed to design sprints without ever using such words. Reports from the rails—leaks in colder weather, viscosity shifts under heavy grades, dust intrusion near the valve body—translated into design changes that drove the next generation of reliability.

If the story ended there, it would already be a triumph. But McCoy’s legacy traveled farther, because it demonstrated something many still need to hear: talent shines even when systems try to dim it. The market learned his name because performance doesn’t check a résumé for prejudice; it checks bearings for friction.

The Cultural Engine: Why “The Real McCoy” Still Matters

Phrases endure when they carry emotional truth, and “the real McCoy” carries the promise that a thing will work when you need it most. It is the opposite of a shortcut, the inverse of a counterfeit. In the age of quick fixes and disposable everything, McCoy’s legacy argues for a different philosophy: if you build a solution that quietly does its job day after day, trust accumulates like interest.

Look across today’s infrastructure and the same principle applies. Hospital devices you never think about because they never fail; software scripts that silently reconcile millions of transactions; safety protocols that prevent the headline that never happens. This is McCoy’s lineage. When maintenance professionals talk about condition-based monitoring, when reliability engineers debate mean time between failures, when safety coordinators build procedures that keep workers out of harm’s way—McCoy’s insight is riding shotgun: If it can be done reliably while the system is running, do it.

A Human Story of Work, Dignity, and Design

The arc of Elijah McCoy’s life is not polished myth; it is the grind of courage. Imagine a trained engineer handed a shovel and told to feed the firebox. Imagine that same engineer coming home after long shifts to sketch, file, and fit tiny channels for oil. Imagine failures—valves that stuck, seals that wept, tolerances that didn’t hold—and the decision to try again because the physics made sense even when the prototype did not. That is the heartbeat of invention.

McCoy’s later years brought both recognition and grief. He and his wife Mary suffered injuries in an auto accident late in life, and Mary passed away. McCoy himself died in 1929, leaving behind an industrial world that had already absorbed his invention so thoroughly that many would forget its origin. But the trains did not forget, and neither did the shops that kept them running. They kept ordering “the real McCoy.”

Lessons for Today’s Builders and Operators

Start at the bottleneck. McCoy invented because stoppages were killing efficiency. He didn’t chase novelty; he chased the constraint that held the system back.

Design for the dirty world. Railroads are heat, dust, vibration, and rain. McCoy’s devices weren’t precious. They were tough.

Make reliability visible. A sight-feed isn’t just elegant; it’s trust under glass. When people can see something working, they maintain it better.

Iterate with field truth. Paper designs bow to shop-floor realities. Feedback from users turned McCoy’s device from good to indispensable.

Protect and share wisely. Patents fostered manufacturing at scale while giving McCoy the leverage to keep improving the design.

A Newsroom Note on Impact

Economic significance: By reducing maintenance stops and protecting bearings, McCoy’s lubricators improved uptime and asset life—the twin pillars of operational economics. Those minutes saved multiplied across thousands of trains and factories, turning into days, then months, then years of regained productivity.

Safety significance: Fewer emergency stops and more predictable maintenance are safety wins. Controls that work without manual intervention reduce exposure to heat, pinch points, and hurried procedures—principles that remain foundational in modern safety programs.

Cultural significance: The phrase “the real McCoy” continues to stand for authenticity and performance. It is, in effect, a quality standard named after the person who made quality a standard.

Closing: The Measure of the Genuine Article

Elijah McCoy’s story is not only about a device; it’s about a stance. He saw a world that asked him to wait, to accept less, to tolerate friction—literal and societal. He answered with a design that refused to stop. And in proving his work in the harshest environments, he didn’t merely change machines. He changed expectations.

In every field where time is money and safety is sacred, the question remains timely: Are we using the real McCoy? Not just the brand name—but the true solution, engineered with care, verified by performance, and durable under pressure.

That is the legacy of Elijah McCoy—engineer, inventor, and the quiet patron saint of things that simply do their job.

A custom editorial-style illustration honoring Elijah McCoy and his iconic lubricating cup has been generated for this article.

If this story inspired you…

Follow me for more long-form features on innovators who changed industries through practical brilliance and unstoppable grit.

Have a figure from history or industry you want covered next? Tell me, and I’ll put them on the front page.

About the Creator

TREYTON SCOTT

Top 101 Black Inventors & African American’s Best Invention Ideas that Changed The World. This post lists the top 101 black inventors and African Americans’ best invention ideas that changed the world. Despite racial prejudice.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.