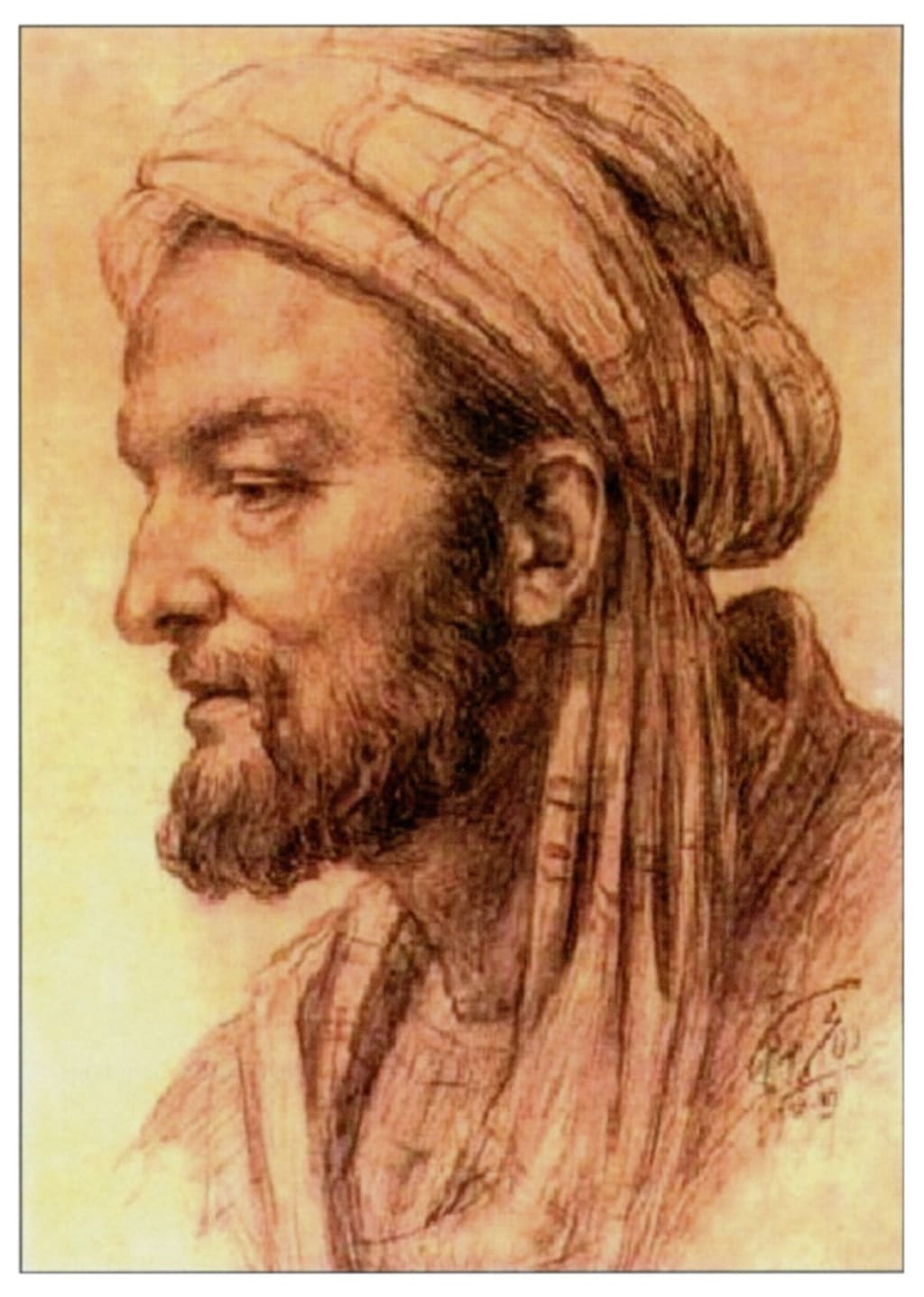

Avicenna (980–1037 CE): Musical Thought Bridging Tradition and Innovation

This study explores Avicenna’s role in shaping musical understanding and explains how his views connect classical heritage with emerging musical perspectives.

Avicenna (980–1037 CE): Musical Thought Bridging Tradition and Innovation

Author: Islamuddin Feroz Former Professor, Department of Music Faculty of Fine Arts, Kabul University, Kabul, Afghanistan

Abstract

Avicenna (980–1037 CE), a prominent Eastern scholar, not only left lasting contributions in philosophy and medicine but also played a significant role in the theory of music and related sciences. By drawing on Al-Farabi’s musical teachings, Greek philosophical and scientific knowledge, and the rich musical experience of Khorasan, he developed a coherent system of music theory that influenced both Eastern and Western music. Avicenna regarded music not merely as an art but as a science connected to mathematics, psychology, and medicine, analyzing the relationship between sound vibrations, human emotions, and mental well-being. This article, using reliable sources, examines his life, education, achievements, and music theories, demonstrating how Avicenna’s teachings strengthened the theoretical foundations of music in Islamic civilization and highlighted their impact on spiritual, educational, and therapeutic development.

Keywords: Avicenna, Music, Music Theory, Al-Farabi, Harmony of Sounds, Islamic Philosophy, Mathematical Sciences.

Introduction

Abu Ali al-Husayn ibn Abdullah ibn Sina, known in the Islamic world as “Sheikh al-Ra’īs” and in the West as “Avicenna,” is one of the most prominent figures in the history of science and human culture. He lived during the fourth and fifth centuries AH, a period marked by scientific and philosophical flourishing in the Islamic lands, especially in Transoxiana. The dynamic scholarly environment of Bukhara and the presence of distinguished teachers provided the conditions for the extraordinary development of Avicenna’s talents. From an early age, he excelled in various sciences and achieved intellectual independence during his adolescence. His knowledge extended beyond medicine and philosophy to include mathematics, logic, natural sciences, and particularly music. Through an interdisciplinary approach, Avicenna established a novel connection between music, psychology, and medicine, thereby making a valuable contribution to the formation of theoretical foundations of music in Islamic civilization.

Music Theory in Avicenna’s Thought

The father of Abu Ali Sina, Abdullah ibn Hasan, was originally from the city of Balkh, a historic city recognized as one of the oldest and most important cultural and scientific centers in northern Afghanistan. Balkh is located approximately 20 kilometers northwest of Mazar-i-Sharif and 74 kilometers south of the Amu Darya River. Throughout history, particularly in ancient times, the city was considered the center of Bactria and is mentioned in historical sources as “Bactra” or “Bactria.” Due to its geographical location and cultural significance, Balkh provided a fertile environment for the growth and development of the scientific and cultural elites of its time, having a significant impact on the education and nurturing of talents in Avicenna’s family, including Abdullah ibn Hasan and his son. The name of this city is also recorded in ancient Greek sources.

According to some sources, Abdullah ibn Hasan moved to Bukhara in 976, and according to others, in 978, during the reign of Amir Nuh ibn Mansur of the Samanid dynasty. Most reputable Islamic and Western sources consider Avicenna’s birthplace to be the village of Afshaneh (or Afshana) near Bukhara in 980 CE (Ismailov, 2018, pp. 14–17). Some authors, especially in older Persian and Tajik sources, regard him as being from Balkh and have given him the nisba “al-Balkhi.” This attribution is primarily based on his family lineage, as his father, Abdullah, was from Balkh, and in some older sources, the family origin was mentioned instead of the exact birthplace. Consequently, the title “Ibn Sina al-Balkhi” occasionally appears in historical texts, referring to his ancestral origin rather than necessarily his actual birthplace.

Abdullah ibn Hasan, the father of Husayn, was a wise man who endeavored to provide his son with proper and comprehensive education. From the age of 14, the young man began independent studies and by 17 had studied all branches of knowledge (Isgandarova, 2016, p. 9). He quickly mastered geometry, astronomy, and music, and eventually became familiar with Aristotle’s metaphysics, which profoundly shaped his scientific path. From the age of 21, he engaged in writing and produced significant works. He spent his early life until around the age of 22 during the final period of Samanid rule (389–395 AH), after which he left Bukhara and continued his life and scholarly activities in the cities of Gorgan, Hamadan, and Isfahan. Therefore, the majority of Avicenna’s scientific and philosophical achievements were developed after the Samanid period, although Bukhara, as the scientific and cultural center of the Samanids, played an important role in nurturing his talents (Flannery, 2025).

Avicenna creatively continued many of the scientific views of his compatriot Al-Farabi, thereby making a significant contribution to the development of various aspects of music theory of his time. In his encyclopedia al-Shifa, Avicenna, relying on Al-Farabi’s ideas of consonant intervals, demonstrated the possibility of converting Pythagorean intervals into pure intervals. Interestingly, this discovery later laid the groundwork for the development of the pure notation system during the European Renaissance. These theoretical achievements not only influenced the development of Eastern music but also formed the foundation for many subsequent advancements in Western music. By combining Greek knowledge with the musical experiences of Khorasan, Avicenna developed a coherent system of music theory that served as a basis for musicians in both the East and the West for centuries (Toshboyeva, 2025, p. 57).

At that time, he was the most influential figure in the arts and sciences of the Islamic world and held titles such as Sheikh al-Ra’īs (Leader of the Wise) and Hujjat al-Haqq (Proof of God), titles by which he is still recognized in the East. From an early age, he demonstrated remarkable talent for learning. By the age of ten, he had mastered the entire Quran as well as Arabic grammar and syntax, and then proceeded to study logic and mathematics under the supervision of Abu Abdullah Natili. After quickly mastering these subjects, he went on to study physics, metaphysics, and medicine with Abu Sahl al-Masih. By the age of sixteen, he was a master of all the sciences of his time (Nasr, 1997, p. 43). Avicenna was not only a great philosopher and physician of the Islamic world but also one of the first scholars to theorize about music, melody, and the harmony of sounds. He devoted a part of his most important work, al-Shifa, to music, considering it a branch of mathematical knowledge and approaching it not only from an artistic and aesthetic perspective but also from a scientific and rational standpoint (Lopez-Farjeat, 2013, p. 84). As evidenced in various works, including al-Shifa, al-Najat, and a treatise attributed to him entitled Maqala fi ‘Ilm al-Musiqi, he presented profound insights into the field of music (Nasr, 1997, p. 32).

Much like Al-Kindi, Avicenna was largely indebted to the general principles of the Pythagorean concept of music and, consequently, accepted that music has a mathematical structure. The Pythagoreans were the first to use the term cosmos to refer to the entirety of everything constituting the universe, and they believed that a mathematical structure underlies the order of the world. Moreover, according to Pythagorean cosmology and metaphysics, harmony governs everything in the cosmos and is specifically reflected in the harmonic ratios of the universe. For this reason, music functions as an explanation of the cosmos (Lopez-Farjeat, 2013, p. 85). In his encyclopedia al-Shifa, a comprehensive work of the sciences of his time, a detailed section is devoted to music. In this section, Avicenna introduces music as a science based on numerical ratios and the harmony of sounds, asserting that the human ear is naturally attuned to numerical order; therefore, simple and regular intervals are more pleasing to it. In al-Najat, a concise summary of al-Shifa, these views are presented in a more condensed and practical form for philosophers and artists (Rosaria, 2025, p. 8).

Avicenna, in explaining the nature of sound, states: “Sound is the rapid vibration of air produced by the impact of a hard or elastic object.” This definition, based on a physical understanding of the phenomenon of sound, demonstrates that he did not consider music merely as an auditory art but approached it scientifically, focusing on the origin and characteristics of sound. He also discussed the duration and intensity of sound, the manner of vibration, and its effect on human hearing—views that were highly advanced and innovative for his time. According to Avicenna, music is an art that has a direct impact on the human soul and body. He considered melodies as agents that evoke various emotions; they can produce joy or sorrow, alleviate mental ailments, and even help balance the humors and temperaments. Therefore, music, in his view, was not only an art but also a form of therapy, a “medicine for the soul.” Avicenna distinguished between rhythm and melody. He believed that iqa‘—the temporal weight and order of notes—must perfectly align with lahn (melody) and intervals to achieve a beautiful and effective musical effect. He classified melodies into “ajnas” and “an’gham” and discussed the composition and structure of maqamat and musical modes in detail (Farmer, 1930, p. 329).

Avicenna’s greatest innovation in the philosophy of medicine was his systematic integration of medicine, psychology, philosophy, and music. In his discussions on education and training, he also assigned a prominent role to music and physical exercise, emphasizing the idea that music has the power to stimulate movement and transform psychological states. According to him, music is a source of pleasure, joy, spiritual purity, and ecstasy, and through musical experience, a child can understand fundamental concepts such as harmony and dissonance, pitch, and the manner in which these sonic ratios occur. By carefully analyzing the natural vibrations and rhythms of the body, such as pulse, heartbeat, and respiration, Avicenna related them to musical intervals and structures. This perspective elevated music in his thought from being merely an art to a therapeutic tool and a branch of medical science. In this way, Avicenna is considered a pioneer in scientifically grounded music therapy (Rosaria, 2025, p. 6). Furthermore, he provided precise descriptions of traditional musical instruments, explaining their structure, tuning, and expressive capacities. His preference for the ghijak, due to its tonal similarity to the human voice, reflects his philosophical view that the human voice is the most noble medium for conveying music (Toshboyeva, 2025, p. 59).

Overall, Avicenna made a highly valuable contribution to at least one branch of the traditional quadrivium, which was music, a field in which he excelled both theoretically and practically. In his music theories, Avicenna followed Al-Farabi closely; both men based their writings on the “music prevalent in their time” and were not merely transmitters of Greek music theory. The fact that they used the “Pythagorean scale” does not imply that they solely followed the theories proposed by Greek authorities, as the pentatonic scale had been in use in China long before historical contact with Hellenic civilization, and it was also found independently in Western Asia without any “Greek influence.” Avicenna studied and interpreted the “performed music theory of Khorasan of his time,” music that has largely been preserved as a continuous classical music tradition to this day. In performances of music in Transoxiana, Afghanistan, and modern-day Iran, one can hear the real sounds upon which Avicenna’s music theories are based (Nasr, 1997, pp. 18–36). From Avicenna’s perspective, music is valuable when it is accompanied by reason and order. He opposed music that pursued only sensory pleasure, believing that a beautiful melody is one that creates harmony among reason, emotion, and human nature. Music, for him, was a tool for cultivating the soul and achieving inner balance. In general, by combining the knowledge of sound physics, mathematical intervals, and the psychology of emotions, Avicenna established the theoretical foundations of music in Islamic civilization. His ideas later inspired prominent musicians such as Safi al-Din al-Urmawi and Abd al-Qadir Maraghi, shaping the theoretical path of music in the Islamic world for centuries.

Avicenna’s Role in Eastern and Western Music

As one of the most outstanding music theorists in the Islamic world, Avicenna made a significant contribution to the development of music in both the East and the West. By combining Greek knowledge, Khorasani musical experience, and Al-Farabi’s teachings, he developed a coherent system of music theory that served as a foundation for musicians for centuries. His works, especially in al-Shifa and al-Najat, demonstrate his deep understanding of intervals, harmony, and the effect of melodies on the human psyche. In Persian-speaking countries, Avicenna’s theories inspired musicians such as Safi al-Din al-Urmawi and Abd al-Qadir Maraghi, shaping the classical music tradition of Khorasan. His works were translated and disseminated throughout the Islamic world, from Iran and Andalusia to the Ottoman Empire. In the Arab world, his ideas in music theory and scientific music education were widely acknowledged, and many academic and philosophical music schools benefited from his works. In Turkic regions, his works, alongside those of Al-Farabi and other thinkers, reinforced the theoretical foundations of traditional Ottoman and Central Asian music (Toshboyeva, 2025, p. 59). Avicenna’s importance is evident not only in theory but also in the practical application of music and coherent musical notation. He considered music a rational science and therapeutic art capable of harmonizing the human soul and body. The influence of his ideas on Western music is also undeniable, particularly in transmitting concepts of harmony and pure intervals, which were later employed during the Renaissance. In this way, Avicenna created a bridge between Eastern and Western music traditions, establishing his position as a theorist and music teacher in Persian, Arab, and Turkic civilizations.

Conclusion

By integrating the knowledge of sound physics, mathematical intervals, and the psychology of emotions, Avicenna reinforced the theoretical foundations of music in Islamic civilization. He viewed music not only as an aesthetic art but also as a rational science and an effective tool for cultivating the soul and enhancing mental health. Avicenna’s perspectives demonstrate that music can play a significant role both in human education and upbringing as well as in the treatment of psychological disorders. His works and theories inspired subsequent generations of great musicians, such as Safi al-Din al-Urmawi and Abd al-Qadir Maraghi, shaping the theoretical and practical course of music in the Islamic world for centuries. Accordingly, Avicenna’s contributions extend beyond philosophy and medicine, and his profound impact on music, psychology, and human development establishes him as one of the most prominent and influential figures in the history of science and art.

References

Flannery, Michael. (2025). Avicenna Persian philosopher and scientist. Fact-checked by The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Last Updated: Sep. 26, 2025 •Article History. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Avicenna

Farmer, Henry George. (1930). Historical Facts for the Arabian musical influence. London: William Reeves 83 chasing Cross Road, Bookseller Limited.

Hossein. (1997). Three Muslim Sages. New York: Published by Caravan Books.

Ismailov, Israel. (2018). Born in Afshan Tashkent. Tashkent: Hilol Media Publishing House.

Isgandarova, Nazila. (2016). Music in Islamic Spiritual Care: A Review of Classical Sources. Emmanuel College of Victoria University. Pp 1-16. https://www.chrysalis-foundation.org/wp- content/uploads/2019/06/07Isgandarova-MusicInIslamicSpiritualCare.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

Lopez-Farjeat, Xavier. (2013). Avicenna on musical Perception. Philosophical Psychology in Arabic thought and the Latin Aristotelianism of the 13TH Century. Pp 84-110. (LÓPEZ-FARJEAT, 2013, p85)

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. (1997). Three Muslim Sages. New York: Published by Caravan Books.

Rosaria, Maria. (2025). Arab Music and Music Therapy: Ibn Sina’s contribution to Music therapy today. Parthenope University of Naples. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/395539414_31_July_25_Arab_Music_and_Music_Therapy_IBN_SINA%27s_contribution_to_Music_therapy_today.

Toshboyeva, M. (2025). On Ibn Sina’s Treatise Kitab Al-Shifa: A Musicological perspective. Modern American Journal of Linguistics, Education, and PedagogyISSN: 3067-7874 Volume 01, Issue 03, June, 2025. Pp 56-60.

About the Creator

Prof. Islamuddin Feroz

Greetings and welcome to all friends and enthusiasts of Afghan culture, arts, and music!

I am Islamuddin Feroz, former Head and Professor of the Department of Music at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Kabul.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.